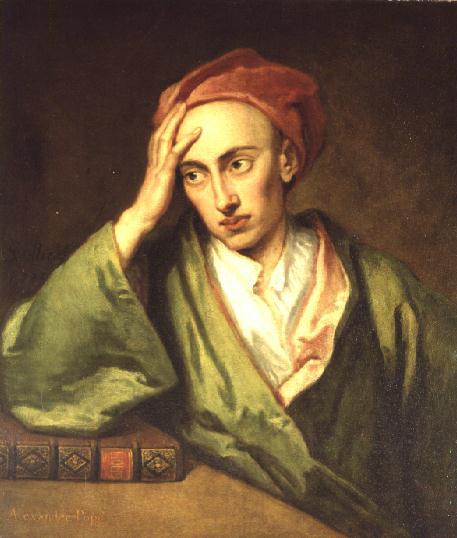

All poets are beautiful. Is Alexander Pope not beautiful?

POPE:

It would be a wild notion to expect perfection in any work of man: and yet one would think the contrary was taken for granted, by the judgment commonly passed on poems. A critic supposes he has done his part, if he proves a writer to have failed in an expression, or erred in any particular point: and can it then be wondered at, if the poets in general seem resolved not to own themselves in any error?

This seems strange: Pope, author of “The Confederacy of Dunces,” himself a poet best known for using his poetry to criticize and excoriate lesser poets, who took sweet delight in crushing denser wits with his superior wit, in this piece of prose, defends poets against harsh criticism. What? Was Pope really soft? In any case, no Critics from the 18th century are even known today, even as one as mighty as Pope seems to fear them. The critics are all forgotten.

But Pope was prophetic: civilization means that poetry is not only read, it is discussed and criticized: but finally the poets prove too thin-skinned, and resolve “not to own themselves in any error,” which is precisely what happened with modern poetry: its desultory prose style simply cannot be measured as faulty; the loose address of an Ashbery is simply beyond criticism. So is every one happy? Would Pope, who rhymes, be?

Next, Pope puts his finger on another modern ailment: poetry is essentially trivial:

I am afraid this extreme zeal on both sides is ill-placed; poetry and criticism being by no means the universal concern of the world, but only the affair of idle men who write in their closets, and of idle men who read there.

Finally, Pope makes further modern remarks regarding the poet in society—the genius does not appear out of the blue; they must grow up to an audience; but how? Most likely even the genius—in the early stages of their career, especially—will be shot down, envied, and hated. Is Pope merely feeling sorry for himself? Critical reception is made of flawed and envious humans, and the best thing the genius can hope for is “self-amusement.” So we are back to “idle men in closets.” We are surprised to find Pope, in his prose, to be self-pitying, sensitive, and quaintly tragic. Pope was the first Romantic. He was Byron’s favorite poet, after all.

What we call a genius, is hard to be distinguished by a man himself—if his genius be ever so great, he cannot discover it any other way, than by giving way to that prevalent propensity which renders him the more liable to be mistaken. The only method he has is appealing to the judgments of others. The reputation of a writer generally depends upon the first steps he makes in the world, and people will establish their opinion of us, from what we do at that season when we have least judgment to direct us. A good poet no sooner communicates his works with the same desire of information, but it is imagined he is a vain young creature given up to the ambition of fame; when perhaps the poor man is all the while trembling with fear of being ridiculous. If praise be given to his face, it can scarce be distinguished from flattery. Were he sure to be commended by the best and most knowing, he is sure of being envied by the worst and most ignorant, which are the majority; for it is with a fine genius as with a fine fashion, all those are displeased at it who are not able to follow it: and it is to be feared that esteem will seldom do any man so good, as ill-will does him harm. The largest part of mankind, of ordinary or indifferent capacities, will hate, or suspect him. Whatever be his fate in poetry, it is ten to one but he must give up all the reasonable aims of life for it. There are some advantages accruing from a genius to poetry: the agreeable power of self-amusement when a man is idle or alone, the privilege of being admitted into the best company…

DANTE:

The author of the Comedia, here in a prose section of his earlier, Beatrice-besotted Vita Nuova, speaks of several apparently unrelated things at once: the poet describing love as if it were a person, the use of high and low speech as it relates to rhyme and love, and how these uses should be understood in a prose manner.

Dante quotes examples in classical poetry (mostly figures of speech) to defend his own practice in his “little book” (the Vita Nuova) of personifying love.

The dramatizing license is all well and good, but Dante also makes the fascinating point that poets began to write in the common tongue (as opposed to literary Latin) in wooing (less educated) females, and that rhyme is best used for love. How does one get one’s head around this radical, grounded, democratic, proto-Romantic notion?

For Dante, poetry and love overlap in a corporeal manner in three ways: personification, rhyme, and wooing, the first belonging to rhetoric, the second, to music, and the third, practical romance. The whole thing is delightfully religious in a mysterious, trinitarian sort of way: Personified love, Christ, the son; Rhyme, the Holy Spirit; and Wooing, the Creative Love of God. Or, on a more pagan religious level, personified love can be any messenger; rhyme, the trappings of religion’s austere/populist articulation; and wooing, the conversion of the poor.

It might be that a person might object, one worthy of raising an objection, and their objection might be this, that I speak of Love as though it were a thing in itself, and not only an intelligent subject, but a bodily substance: which, demonstrably, is false: since Love is not in itself a substance, but an accident of substance.

And that I speak of him as if he were corporeal, moreover as though he were a man, is apparent from these three things I say of him. I say that I saw him approaching: and since to approach implies local movement, and local movement per se, following the Philosopher, exists only in a body, it is apparent that I make Love corporeal.

I also say of him that he smiles, and that he speaks: things which properly belong to man, and especially laughter: and therefore it is apparent that I make him human. To make this clear, in a way that is good for the present matter, it should first be understood that in ancient times there was no poetry of Love in the common tongue, but there was Love poetry by certain poets in the Latin tongue: amongst us, I say, and perhaps it happened amongst other peoples, and still happens, as in Greece, only literary, not vernacular poets treated of these things.

Not many years have passed since the first of these vernacular poets appeared: since to speak in rhyme in the common tongue is much the same as to speak in Latin verse, paying due regard to metre. And a sign that it is only a short time is that, if we choose to search in the language of oc [vulgar Latin S. France] and that of si, [vulgar Latin Italy] we will not find anything earlier than a hundred and fifty years ago.

And the reason why several crude rhymesters were famous for knowing how to write is that they were almost the first to write in the language of si. And the first who began to write as a poet of the common tongue was moved to do so because he wished to make his words understandable by a lady to whom verse in Latin was hard to understand. And this argues against those who rhyme on other matters than love, because it is a fact that this mode of speaking was first invented in order to speak of love.

From this it follows that since greater license is given to poets than prose writers, and since those who speak in rhyme are no other than the vernacular poets, it is apt and reasonable that greater license should be granted to them to speak than to other speakers in the common tongue: so that if any figure of speech or rhetorical flourish is conceded to the poets, it is conceded to the rhymesters. So if we see that the poets have spoken of inanimate things as if they had sense and reason, and made them talk to each other, and not just with real but with imaginary things, having things which do not exist speak, and many accidental things speak, as if they were substantial and human, it is fitting for writers of rhymes to do the same, but not without reason, and with a reason that can later be shown in prose.

That the poets have spoken like this is can be evidenced by Virgil, who says that Juno, who was an enemy of the Trojans, spoke to Aeolus, god of the winds, in the first book of the Aeneid: ‘Aeole, namque tibi: Aeolus, it was you’, and that the god replied to her with: Tuus, o regina, quid optes, explorare labor: mihi jussa capessere fas est: It is for you, o queen, to decide what our labours are to achieve: it is my duty to carry out your orders’. In the same poet he makes an inanimate thing (Apollo’s oracle) talk with animate things, in the third book of the Aeneid, with: ‘Dardanidae duri: You rough Trojans’.

In Lucan an animate thing talks with an inanimate thing, with: ‘Multum. Roma, tamen debes civilibus armis: Rome, you have greatly benefited from the civil wars.’

In Horace a man speaks to his own learning as if to another person: and not only are they Horace’s words, but he gives them as if quoting the style of goodly Homer, in his Poetics saying: ‘Dic mihi, Musa, virum: Tell me, Muse, about the man.’

In Ovid, Love speaks as if it were a person, at the start of his book titled De Remediis Amoris: Of the Remedies for Love, where he says: ‘Bella mihi, video, bella parantur, ait: Some fine things I see, some fine things are being prepared, he said.’

These examples should serve to as explanation to anyone who has objections concerning any part of my little book. And in case any ignorant person should assume too much, I will add that the poets did not write in this mode without good reason, nor should those who compose in rhyme, if they cannot justify what they are saying, since it would be shameful if someone composing in rhyme put in a figure of speech or a rhetorical flourish, and then, being asked, could not rid his words of such ornamentation so as to show the true meaning. My best friend and I know many who compose rhymes in this foolish manner.

Pope, the great poet, already, in the 18th century, as a philosopher, has that Modernist smell of trivializing apology about him. Not so Dante, who is an ardent, mysterious flame burning on the candle of the Muse.

WINNER: DANTE

Dante will face Plato in the Classical Final for a spot in the Final Four!