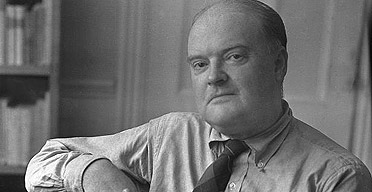

Edmund Wilson, who bullied his way into the Sweet 16: Yea, I’m an asshole, what of it? he seems to be saying. In Letters, arrogance goes a long way.

EDMUND WILSON VERSUS NORTHROP FRYE

Wilson (d. 1972) was a magnificent snob, believing himself above government, morality, tact, and popular literature. He didn’t pay taxes for 10 years after World War Two and got off with a slap on the wrist. He served on the Dewey Commission in the 1930s, an elaborate effort by a few American intellectuals to clear Trotsky against the Soviet findings of the Moscow Trials. Trotsky wrote the following re: the Commission:

The Moscow trials are perpetrated under the banner of socialism. We will not concede this banner to the masters of falsehood! If our generation happens to be too weak to establish Socialism over the earth, we will hand the spotless banner down to our children. The struggle which is in the offing transcends by far the importance of individuals, factions and parties. It is the struggle for the future of all mankind. It will be severe, it will be lengthy. Whoever seeks physical comfort and spiritual calm let him step aside. In time of reaction it is more convenient to lean on the bureaucracy than on the truth. But all those for whom the word ‘Socialism’ is not a hollow sound but the content of their moral life – forward! Neither threats nor persecutions nor violations can stop us! Be it even over our bleaching bones the truth will triumph! We will blaze the trail for it. It will conquer! Under all the severe blows of fate, I shall be happy as in the best days of my youth! Because, my friends, the highest human happiness is not the exploitation of the present but the preparation of the future.

“It is the struggle for the future of all mankind. It will be a severe, it will be lengthy. Whoever seeks physical comfort and spiritual calm let him step aside.”

These are indeed fighting words. “Give up physical comfort” to spread Socialism over the face of the earth. “It will conquer!” Etc. Here’s the world which Wilson, Princeton man, snobby blue blood and literary critic, swore by and lived in. One can say, “despite his pedigree, Wilson was fighting for the salt of the earth,” or, Wilson was a dangerous political lunatic, who thanks to his pedigree, was able to do as he pleased.” Take your pick.

Wilson dismissed J. R. Tolkien as “juvenile,” and asked Anais Nin to marry him, claiming he would teach her how to write. Wilson was interested in “Symbolist” literature, a genre which cannot be defined; those like Wilson, who were interested in it, claimed it was post-Romantic. Wilson, a typical Modernist, defined Romanticism as something silly which preceded Realism. Wilson’s opinion of Poe was that Americans were too “provincial” to appreciate him, unlike Wilson himself, who thought Poe “insane” and whose whole understanding of Poe was that Poe was a bridge between Romanticism and Symbolism—which is ignorant. We always hear that Wilson had “many wives and many affairs,” but why any woman would be interested in this pompous hack is hard to fathom. My guess is that he tried to have affairs and they came to eventually be reported as affairs. He could get literary women published, since he was a well-connected reviewer; perhaps he had personal charisma; perhaps his socialist opinions made him seem gallant with a certain set. His writing is pedantic, dreary, worthless. A writer who believes in world socialism and makes Baudelaire his specialty has to be suspect. Wilson hung around Edna Millay a great deal; it calls to mind for us Yeats and Maude Gonne: great women harmed by politically motivated men who did more than admire them. Millay was a thousand times the genius Wilson—the more worldly—was.

Northrop Frye, unlike Edmund Wilson, was not worldly. He was merely a professor, and a very good one. He came under scrutiny from the Canadian government for his opposition to the Vietnam War, but Frye’s influence was chiefly literary.

Frye’s influence can be summed up this way: Harold Bloom. Criticism eclipses Reviewing. Useless and pretentious literature gets a free pass because it fits into the professor’s “scientific” view of literary “tradition.” Frye, like Bloom, excuses all sorts of nuttiness in the name of Profound Scholarship. One doesn’t read a book. One takes a book and fits it into an ever-changing tradition that includes the Bible and various texts throughout recorded history, in a way that changes those texts: modernism, as invented by its godfather, T.S. Eliot. The one thing that is not allowed is common sense. The unstable and the ‘highly significant’ rule. Reality as understood in a populist context is forbidden.

Edmund Wilson falsely presented himself as an authority on the Dead Sea Scrolls, in order to “upset” theological authority. Frye/Bloom has the same ambition, a bold one. Confuse, and then attempt to be influential within that confusion. Literature as Fabricated Contemporary Religious Scholarship. Literature, for the Ambitious Modernist Critic, is not something which comes into the life of someone who peruses a story or a poem for a half an hour from its beginning to its end, the story or poem succeeding or failing on its own terms. Literature is rather a vast joint corporate enterprise which demands abstract expert-ism as far removed from the ordinary reading experience as possible. Welcome to John Crowe Ransom’s “Criticism, Inc.” Welcome to Harold Bloom’s “Anxiety.” Welcome to Edmund Wilson’s “Symbolism.” Welcome to Northrop Frye’s “Science.”

Words, words, words.

WINNER: EDMUND WILSON

*

HELENE CIXOUS VERSUS J.L. AUSTIN

Austin exists in the present, with his theory of performative language: language, in the most radical sense imaginable, does not mean; it does.

Cixous (pronounced seek-soo, or ‘looking for Sue’) exists in the past, since her work comes out of her academic success in the radical 60s and 70s in France, when French Writing (Ecriture) Theory exploded onto the scene, casting aside German Idealism and Anglo-American pragmatism as the sexiest thing around. Why sexy? Why the past? Because Western Tradition had repressed everything that was not Male and Ideal; and now Cixous was ‘writing’ the ‘female body’ in order to redeem the past—which clings to the effort.

Austin worked for British intelligence; in him, Anglo-American pragmatism, in its smug complacency, triumphs over the French Theory and the Freud and the Feminism and the Derrida and the Lacan of Cixous—who finally over-argues her case.

If the goal of the woman is to triumph over her mere flesh, while the man’s ambition is to reduce the woman to mere flesh for his pleasure, it is clear that feminist projects which rely on dualisms of past/present, A/not A, penis/no penis, male/female, light/darkness, many/one, speech/language, West/East, body/mind, beautiful/ugly, are doomed to fail, for even with conscious efforts to subvert these dualisms, the French Theorist either remains trapped in them, or drifts off into over-heated incoherence.

Austin, by showing that language is performance, brought flesh to language in a way the French Theorists, with their deferrals of meaning and their difference, could never quite pull off; non-gendered flesh, too, and thus deliciously feminist/not feminist.

WINNER: AUSTIN

*

EDWARD SAID VERSUS SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR

The one overwhelming thing which Modernism did, and here we include everything, whether it is the feminism of a De Beauvoir or the postcolonial historicism of a Said, was the squashing of sincerity.

Is sincerity a good in itself?

If it is naive, and based in ignorance, if it lacks irony or a sense of humor, they will say sincerity verges on stupidity.

We speak of a useful sincerity, however, free of pain, which, even within its “stupidity,” has the potential to abide and achieve and discover hidden good.

There is a kind of false and bitter “sincerity” which depends on a surrounding insincerity for its existence, an energy possessed by the socialist who needs to convert the world to its vision of simple good, for example. But such ‘save-the-world’ proselytizing is rarely sincere. It assumes too much insincerity in the other.

The kind of sincerity which Modernity has destroyed is the pure and simple kind, guided by love and hope and innocence, neither afflicted nor distracted by deep anxieties or doubts.

This type of sincerity, we imagine, is at the heart of Mozart’s music, and any sustained action of genius: naive, focused, splendid, unique, human, alone, happy.

At first blush, this good type of sincerity is described (and attacked) as sentimentality. The cynic dare not call it stupidity, for the cynic is well aware of how everything is stupid or ‘not what it seems,’ this knowledge characterizing the unsentimental cynic in the first place.

Simone De Beauvoir had to attack sentimentality to ‘free’ women from the dire effects of Victorian romance. For Said, the citizens of the West had to be made aware of the blood on their hands—not just employees of the East India Company—everyone is somehow guilty.

Sentimentality as it existed in the 19th century in the great writings of the Romantics and even in writers like Wilde, who used his wit to keep the spirit of the Romantics alive, was banished in the 20th century, and with it, the more important, and more beneficial, sincerity; the sincerity which stimulates people in a reciprocating atmosphere of cheerfulness and good withers, as churlish cynicism triumphs among the self-aware, chattering classes.

Stupidity of the brain is sometimes necessary for wisdom in the heart.

As De Beauvoir writes:

To recognize in woman a human being is not to impoverish man’s experience: this would lose none of its diversity, its richness, or its intensity if it were to occur between two subjectivities. To discard the myths is not to destroy all dramatic relation between the sexes, it is not to deny the significance authentically revealed to man through feminine reality; it is not to do away with poetry, love, adventure, happiness, dreaming. It is simply to ask, that behavior, sentiment, passion be founded upon the truth.

She protests too much.

Said, who spent his childhood in the British colony of Palestine, wrote:

Too often literature and culture are presumed to be politically, even historically innocent; it has regularly seemed otherwise to me, and certainly my study of Orientalism has convinced me (and I hope will convince my literary colleagues) that society and literary culture can only be understood and studied together. In addition, and by an almost inescapable logic, I have found myself writing the history of a strange, secret sharer of Western anti-Semitism. That anti-Semitism and, as I have discussed it in its Islamic branch, Orientalism resemble each other very closely is a historical, cultural, and political truth that needs only to be mentioned to an Arab Palestinian for its irony to be be perfectly understood.

The genie is out of the bottle. Not only is war impossible, peace and reason are, too. Where the phrase “anti-Semitism” exists, sincerity cannot exist. Luckily, one can get back a certain amount of sincerity by stepping off the stage, putting aside certain books, and ignoring certain individuals. But the problem with the landscape remains.

WINNER: SAID

*

SARTRE VERSUS HAROLD BLOOM

We expect critics to be critical. As Northrop Frye has said, we can’t teach literature, only the criticism of literature, and this is why so many poets hate critics—precisely because critics are critical in Frye’s sense. And, since Frye is correct, Criticism dominates learning, our learning, whether we want it to, or not. And more than this, Criticism writes our poetry, as well. Wilde and Poe both explicitly stated the obvious: the critical sense is what writes the poetry; the so-called creative or imaginative faculty is merely the critical faculty reversed. Criticism does not create, it judges; exactly, and the creative faculty does not create either (only God does)—the creative faculty combines; and every moment of the combining process is effected by the judgment, by the critical intelligence of the artist.

Harold Bloom is a successful critic for the same reason Poe was a successful critic: a host of minor poets strongly dislike them. Bloom pursues the logic laid out here by vilifying Poe and championing Emerson; Poe’s test was more severe: one was less a critic if one was not a poet (Bloom is not) while Emerson’s test simply said that any strong argument was poetry. Poe’s rivalry is something Bloom cannot face. Bloom is therefore not critical, precisely because his critical choices are driven by the fact that he is not a poet himself—which fulfills the prophecy.

Sartre is too anti-Literature to be a poet or a critic; Sartre is like Bloom, then, but one who knocks over Bloom’s chess pieces, even as Sartre agrees with Emerson that argument is finally all. Listen to Sartre here:

There is no ‘gloomy literature,’ since, however dark may be the colors in which one paints the world, one paints it only so that free men may feel their freedom as they face it. Thus, there are only good and bad novels. The bad novel aims to please by flattering, whereas the good one is an exigence and an act of faith. But above all, the unique point of view from which the author can present the world to those freedoms whose concurrence he wishes to bring about is that of a world to be impregnated always with more freedom. One can imagine a good novel being written by an American negro even if hatred of the whites were spread all over it, because it is the freedom of his race that he demands through his hatred. But nobody can suppose for a moment that it is possible to write a good novel in praise of anti-Semitism. For, the moment I feel that my freedom is indissolubly linked with that of all other men, it cannot be demanded of me that I use it to approve the enslavement of a part of these men. Thus, whether he is an essayist, a pamphleteer, a satirist, or a novelist, whether he speaks of individual passions or whether he attacks the social order, the writer, a free man addressing free men, has only one subject—freedom.

Sartre is still playing chess, with white and black pieces, even though some have run away in an attempt to be “free.” Bloom plays a more elaborate game of chess, one that keeps the pieces upright, even as we have no idea how the game is proceeding, though we do know Shakespeare is Bloom’s king and Emerson, the queen, perhaps. Literature can be ‘too gloomy’ for Bloom—he accused Poe of precisely this, even as he praised Emerson’s health and clarity. But those who accuse Poe of playing too much in a minor key tend to be those who play in no key at all and instead do a lot of thumping: Sartre thumps very loudly in order to flatter a certain sensibility. Bloom sings fragmented medleys, flattering in a far more rarefied fashion.

WINNER: BLOOM

The last of the women—de Beauvoir and Cixous—have fallen!

The Post-Modern bracket is now Wilson, Austin, Said, and Bloom!