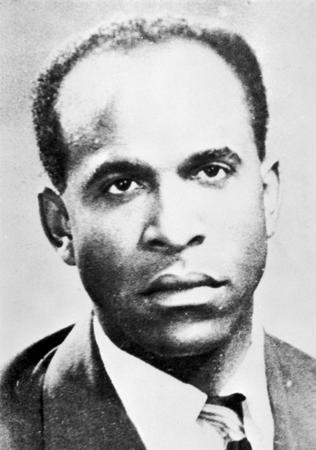

Fanon: Saw 9/11 coming in the 1950s

AUSTIN:

Philosophers have assumed utterances report facts or describe situations truly or falsely. In recent times this kind of approach has been questioned—in two stages.

If things are true or false it ought to be possible to decide which they are, and if we can’t decide which they are, they aren’t any good but are, in short, nonsense.

Secondly: people began to ask whether statements dismissed as nonsense were really statements after all. Mightn’t they perhaps be intended not to report facts but to influence people in this way or that, or to let off steam in this way or that? Or perhaps these utterances drew attention in some way (without actually reporting it) to some important feature of the circumstances in which the utterance was being made? On these lines people have now adopted a new slogan, the slogan of the ‘different uses of language.’ The old approach, the old statemental approach, is sometimes called even a fallacy, the descriptive fallacy.

I want to discuss a kind of utterance which looks like a statement and grammatically, I suppose, would be classed as a statement, which is not nonsensical, and yet is not true or false. These are not going to be utterances which contain curious verbs like ‘could’ or ‘might,’ or curious words like ‘good,’ which many philosophers regard nowadays as danger signals. They will be perfectly straightforward utterances, with ordinary verbs in the first person singular present indicative active, and yet we shall see at once that they couldn’t possibly be true or false. Furthermore, if a person makes an utterance of this sort we should say that he is doing something rather than merely saying something.

When I say ‘I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth’ I do not describe the christening ceremony, I actually perform the christening.

If I say ‘I congratulate you’ when I’m not pleased or when I don’t believe the credit was yours, then there is insincerity.

If I say something like ‘I shall be there,’ it may not be certain whether it is a promise, or an expression of intention, or perhaps even a forecast of my future behavior, of what is going to happen to me; and it may matter a good deal, at least in developed societies, precisely which of these things it is.

By means of these explicit performative verbs and some other devices we make explicit what precise act it is that we are performing when we issue our utterance. But here I would like to put in a word of warning. We must distinguish between the functions of making explicit what act it is we are performing, and the quite different matter of stating what act it is we are performing.

Consider the case, however, of the umpire when he says ‘Out.’ Performing has some connection with the facts.

Statements, we had it, were to be true or false; performative utterances on the other hand were to be felicitous or infelicitous. They were doing something, whereas for all we said making statements was not doing something. Now this contrast surely, if we look back at it, is unsatisfactory.

Ills that have been found to afflict statements can be precisely paralleled with ills that are characteristic of performative utterances. And after all when we state something or describe something or report something, we do perform an act which is every bit as much an act as act of ordering or warning.

FANON:

The national middle class which takes over power at the end of the colonial regime is an underdeveloped middle class. It has practically no economic power, and in any case it is in no way commensurate with the bourgeoisie of the mother country which it hopes to replace.

Colonialism pulls every string shamelessly, and it is only too content to set at loggerheads those Africans who only yesterday were leagued against the settlers. The idea of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572 massacre of Protestants in Paris) takes shape in certain minds , and the advocates of colonialism laugh to themselves derisively when they hear magnificent declarations about African unity. Inside a single nation, religion splits up the people into different spiritual communities, all of them kept up and stiffened by colonialism and its instruments. Totally unexpected events break out here and there. In regions where Catholicism or Protestantism predominates, we see the Moslem minorities flinging themselves with unaccustomed ardor into their devotions. The Islamic feast-days are revived, and the Moslem religion defends itself defends itself inch by inch against the violent absolutism of the Catholic faith. Sometimes American Protestantism transplants its anti-Catholic prejudices into African soil, and keeps up tribal rivalries through religion.

Austin is not well-known, which is a pity, for this brainy, nerdy, Harvard/Oxford/military intelligence 1940s-1950s professor is very easy to understand and articulates the crucial idea about language which goes to the heart of every philosophical debate from Nietzsche to Wittgenstein to Derrida; linguistic theory, poetry, science and religion cannot be understood without understanding what Austin is talking about in the brief excerpts above: All language is performance. This is Austin’s conclusion. Language doesn’t lie or tell the truth—it does things, and it does things whether or not it lies or tells the truth. Language poetry comes out of this whole notion that language is performance. But in a misguided manner, since language poetry is so awful, and since the poets have always understood that poetry is precisely that which is neither true nor false, and yet is not nonsense—due to both its pleasurable effect and its grammatical epistemology.

Fanon confines himself to the facts of colonialism—a completely different topic one would think, but not really: “Moslem minorities flinging themselves with unaccustomed ardor into their devotions” is a prophecy of 9/11 made in the 1950s. Religion—the realm where language is performance—dominates politics, or, it might be said, is politics, and always will be. Liberalism has unconsciously known this, and its victories in the university and in Washington—uneasy, dumbing-down, ravenous sorts of victories, threatening to collapse all that Liberalism ostensibly stands for—are due precisely to this knowledge. If science and democracy often seem irrational, this is why.

WINNER: AUSTIN