Doesn’t it all finally come down to this?

Is your fiction a lie, or is it art?

If fiction is a mere lie, you have no right to call it art, and if you do, you and your art are a sham. Sorry.

If your fiction is not a lie, then it is not fiction, but truth, and even here, your art, your fiction, is a lie and a sham—because all you are doing is telling the truth, or, not lying, not producing fiction, producing fact, not art. Sorry, again.

So art must be a lie, but when does that lie stop being a sham?

When does a lie become what we have come to praise as art?

First we must ask: why is a lie a bad thing? Because it deceives. So the fiction writer (or poet) does not lie, even though he lies, because the reader knows he is lying. There is no deception.

Unless, unless…we cry when we read a poem: then our feelings have been deceived. We talk of honest feeling, sincere feeling, as a good.

So here we see art deceiving our feelings. But if feelings respond to a sentimental message, has deception really occurred? Who, or what, has been deceived, when a poem or a movie makes us cry? Our feelings have been deceived, but have we been deceived? We still know the poem is a lie, even as it makes us cry. So no real deception has occurred.

Let’s look at it this way: if the poet tells the truth, and the reader believes it is a lie, the truth is a lie, for the reader, not just the reader’s feelings, has been deceived.

So it isn’t an issue at all of truth or lies, but deception.

We, as readers of fiction, do not—cannot—know the lies of fiction as truth; what really happens is that all fiction is a mixture of lies and truth, and the truth is what we truly understand.

If we are not deceived, there is no lie.

No reader can be deceived by the truth, for truth, by its nature, cannot deceive; and therefore no reader ever believes, or can believe, that fiction worth reading is a lie. Fiction always moves us with its truth; it moves us when it does not deceive us; and therefore when fiction is art, when fiction is valid and good and successful, it succeeds entirely as truth.

And yet…we all know that an explanation, leaving out one small detail, can serve an entirely different purpose, that one detail taken away can turn a truth into a lie. How then, can the mixture of lies and truth, then, equal truth for the reader of fiction?

The answer to this dilemma lies in the difference between life and fiction. Life contains lies and truth. Fiction contains nothing that can be called either lies or truth.

Life is open-ended and interested. Fiction is closed and disinterested. A lie in life has real consequences. A lie in fiction has none. If a lie in fiction has no consequences, it does not deceive. If it does not deceive, it must be true, or, at least have no lies. The mixture of lies and truth in fiction produces something which cannot deceive the reader, because the reader is assuming the fiction is not true. But we care only about truth and are able to extract it from the fiction. The truth-within-the-fiction is what the reader is actually reading, actually knowing. Life presents truth and lies as either-or. Fiction presents truth and lies as one-within-the-other.

In fiction, it is not that it doesn’t matter if it’s a lie, or a truth. It’s just that lies or truth, as an either-or, cannot exist in fiction. Fiction, as fiction, does not deceive. The feeling that life is constantly deceiving us makes us run to fiction—which cannot deceive us. If fiction affects our feelings, we rejoice in feeling superior to our mere feelings, which are deceived, for the failure of the feelings to detect the truth only reaffirms that we are not deceived.

The extraction of truth from lies is where the “art” of fiction is truly located.

The “art” of a good detective is the same as the “art” of good fiction—as it’s read, or written. The “art” of a “good” detective is necessary—when the criminal is “good.” The writing and reading of good fiction, likewise, depend on one another.

Detection is the key.

Plato was correct. We argue with Socrates in vain.

Fiction is bad, and is always bad. Good fiction does not succeed because of its fiction, but because of its truth. And the extraction or detection of that truth is the art of fiction.

The great writer of fiction disrupts the fictional reading of fiction by the reader who is helplessly running away from life and its deceptions to the drug of fiction, and makes the detection and the extraction of truth the attribute that matters.

We may extract the truth by our response to beauty. We may extract the truth by looking beyond the work to ourselves, or to implications outside the work. It is not for us to say how the truth is extracted, only that the chief importance lies in the faculty of detection itself.

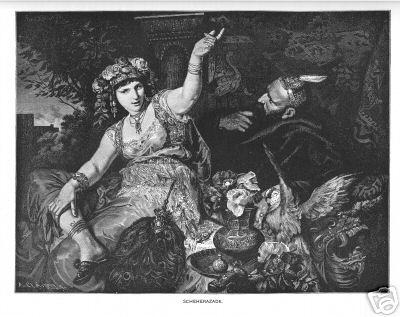

The American author who elevated Criticism, discovered the Big Bang, was a short fiction master, a code-breaker, invented the unreliable narrator, detective fiction, science fiction, and invented modern humor, besides, made it a paramount concern of his to imply that his fiction was not fiction at all. The “inventor of modern humor” may seem a stretch, since we are talking of Edgar Allan Poe, but let us quote from one of his more obscure tales, “The Thousand and Second Tale of Scheherazade.” We make an example of this tale for the way it presents the relationship between truth and fiction.

The premise is simple: Poe makes use of the narrative device which frames the Arabian Nights:

It will be remembered, that, in the usual version of the tales, a certain monarch, having good cause to be jealous of his queen, not only puts her to death, but makes a vow, by his beard and the prophet, to espouse each night the most beautiful maiden in his dominions, and the next morning to deliver her up to the executioner.

Having fulfilled this vow for many years to the letter, and with a religious punctuality and method that conferred great credit upon him as a man of devout feelings and excellent sense, he was interrupted one afternoon (no doubt at his prayers) by a visit from his grand vizier, to whose daughter, it appears, there had occurred an idea.

Her name was Scheherazade, and her idea was, that she would either redeem the land from the depopulating tax upon its beauty, or perish, after the approved fashion of all heroines, in the attempt.

The twist Poe adds is equally simple: after her life is saved, he has Scheherazade tell one more tale, based on amazing facts of real life; the king, finding the truth too absurd to believe, has her killed, then, after all.

Scheherazade merely refers to modern scientists and engineers as “magicians” and the king, listening to it as a story, simply cannot swallow it.

“ ‘Another of these magicians, by means of a fluid that nobody ever yet saw, could make the corpses of his friends brandish their arms, kick out their legs, fight, or even get up and dance at his will. Another had cultivated his voice to so great an extent that he could have made himself heard from one end of the earth to the other. Another had so long an arm that he could sit down in Damascus and indite a letter at Bagdad — or indeed at any distance whatsoever. Another commanded the lightning to come down to him out of the heavens, and it came at his call; and served him for a plaything when it came. Another took two loud sounds and out of them made a silence. Another constructed a deep darkness out of two brilliant lights. Another made ice in a red-hot furnace. Another directed the sun to paint his portrait, and the sun did. Another took this luminary with the moon and the planets, and having first weighed them with scrupulous accuracy, probed into their depths and found out the solidity of the substance of which they were made…

“Preposterous!” said the king.

We love this reference to photography: “Another directed the sun to paint his portrait, and the sun did.”

Aristotle: “Not to know that a hind has no horns is a less serious matter than to paint it inartistically.”

Poe affixes the old saying, “Truth is stranger than fiction” to the head of his Scheherezade tale.

Again, from Aristotle’s Poetics: “With respect to the requirement of art, the probable impossible is always preferable to the improbable possible.”

When it comes to truth being “stranger,” in the Aristotelian formula, “strange” is “improbable possible.” But “directed the sun to paint his portrait, and the sun did” seems “probable impossible,” too.

Science would make it clear to the ancient caliph how photography works, how the “sun can paint a portrait.”

But in the fiction, the “magician” directs the sun to paint his portrait, which is a “probable impossible,” a “requirement of art” for Aristotle. But it fails for Poe’s Scheherezade; the king finds it “improbable,” and thus rejects it. The joke, of course, is that Poe knows—and the reader may know—or does know, when he consults the footnotes—that the science exists, and therefore it is not only probable and possible; it is.