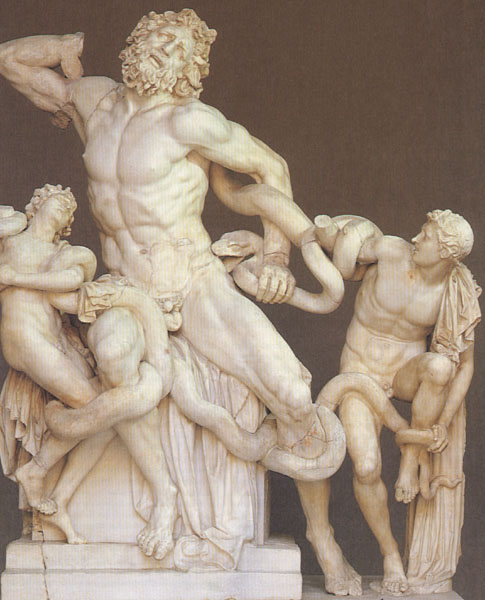

Laocoon: his screams are terrifying in Virgil’s poem; the sculptor’s single moment only sighs.

All are welcome here at Scarriet:

The amateur, full of common sense, and curiosity, and feelings…

The philosopher, with ideas and rigor and rules…

The critic, with precise means to make better art and to judge honestly…

And lastly, the genius of invective—for what recourse, other than invective, has the genius, surrounded by proud sheep?

An all-consuming love for the divine poetry is the reason Scarriet exists—but we do more than love; we search for principles; we love to attack the enemies of art and poetry and taste, and to rummage through ancient literature to find wisdom that is lost.

This leads us to make two crucial points—each with a caveat.

1. Moderns (that’s us) tend to think that everything we are doing and everything worth doing, is new. This, unfortunately, is more than just ignorant: it is an active impediment to the enjoyment of art.

This is not to say that the ancients are smart and the moderns are stupid. We only caution against 1) the new which is not really new and simply because many believe it is new, becomes an excuse for a certain kind of jackass-ism.

2. As moderns, we are victimized by another monstrous idea: that all constraint (which translates as Taste) is bad, with Plato, the first villain. We can just do anything is our motto—the worst idea for art.

It needs to be understood here that by “constraint,” we do not mean that less is more. Sometimes less is not enough. A half-hearted effort will fit the motto “We can just do anything,” but the effort that is meager needs to be expanded, or withdrawn from public view. Constraint here can also mean: “show constraint when making art public. If it’s not good enough, don’t waste the public’s time.”

One sometimes hears the phrase, “constraint-based literature,” but all art is guided by constraint: from the frame on a picture to the length of a sonnet to details left out when telling a story. Even Keats’ description of good poetry, “fine excess,” is but an illusion of excess—there is no excess in good art.

Talk of “constraint” makes most moderns uneasy, however, especially when it comes to making their art public. First, we are now in the grip of “therapy” mania: all artistic expression, whether the art is bad or good, is deemed therapeutic, so let it all hang out. And secondly, since so much of the public is indifferent to fine art, and consumes only trash, telling the artist or the poet to show constraint in making their art public seems almost philistine, and unnecessarily censorious.

Constraint, however, is central to beauty, taste, and art, and if the public isn’t given it, they will turn away from art, and trash will win, and art will die, and therapy will be all that’s left. Poets will advise poets, and meanwhile there will be no audience for the poet anymore. Is this what we want?

We wish at this time to introduce our readers to Lessing’s Laocoon: An Essay upon the Limits of Painting and Poetry. The first rather lengthy passage quoted shows Lessing ‘gets it’ when it comes to constraint. Let us listen to this 18th neo-classical philosopher on the visual arts:

…among the ancients beauty was the supreme law of the imitative arts.

…There are passions and degrees of passion whose expression produces the most hideous contortions of the face…as to destroy all the beautiful lines that mark it when in a state of greater repose. These passions the old artists either refined altogether from representing, or softened into emotions which were capable of being expressed with some degree of beauty.

Rage and despair disfigured none of their works. I venture to maintain that they never represented a fury. Wrath they tempered into severity. In poetry we have the wrathful Jupiter, who hurls the thunderbolt; in art he is simply the austere.

Anguish was softened into sadness. Where that was impossible, and where the representation of intense grief would belittle as well as disfigure, how did Timanthes manage? There is a well-known picture by him of the sacrifice of Iphigenia, wherein he gives to the countenance of every spectator a fitting degree of sadness, but veils the face of the father, on which should have been depicted the most intense suffering. This has been the subject of many criticisms. “The artist,” says one, ” had so exhausted himself in representations of sadness that he despaired of depicting the fathers’s face worthily.” “He hereby confessed,” says another, “that the bitterness of extreme grief cannot be expressed by art.” I, for my part, see in this no proof of incapacity in the artist or his art. In proportion to the intensity of feeling, the expression of features is intensified, and nothing is easier than to express extremes. But Timanthes knew the limits which the graces have imposed upon his art. He knew that the grief befitting Agamemnon, as father, produces contortions which are essentially ugly. He carried expression as far as was consistent with beauty and dignity. Ugliness he would gladly have passed over, or have softened, but since his subject admitted of neither, there was nothing to do but veil it. What he might not paint he left to be imagined. That concealment was in short a sacrifice to beauty; an example to show, not how expression can be carried beyond the limits of art, but how it should be subjected to the first law of art, the law of beauty.

Lessing says the artist Timanthes was wise to cover not Agamemnon’s grief, but the ugly expression of it. Lessing then admits that moderns have “enlarged the realm of art,” and “beauty” is no longer the only consideration, but Lessing still looks for laws to apply to the visual arts: the painting or sculpture lives forever in a single instant, which due to “ever-changing nature,” must represent the action prior to its culmination. Constraint is never practiced for its own sake, but for a strong effect. Abstract painting, then, is not only bereft of pictorial representation, but time, as well. da Vinci was correct, perhaps, to make perspective, not color, the key to art, and to call color-lovers simpletons. When ancient painting relied on famous stories for its subject matter, poetry and painting were natural allies—both arts were obsessed with story arc, perspective, and movement. Genius in both poetry and painting once belonged to seeing. To see is not merely to ‘ look at,’ but to become one with nature. By comparison, art and poetry today do a great deal of clever thinking in darkness. But let’s cut short our rant to hear Lessing once more:

…But, as already observed, the realm of art has in modern times been greatly enlarged. Its imitations are allowed to extend over all visible nature, of which beauty constitutes but a small part. Truth and expression are taken as its first law.

…Allowing this idea to pass unchallenged at present for whatever it is worth, are there not other independent considerations which should set bounds to expression, and prevent the artist from choosing for his imitation the culminating point of any action?

The single moment of time to which art must confine itself will lead us, I think, to such considerations. since the artist can use but a single moment of ever-changing nature, and the painter must further confine his study of this one moment to a single point of view, while their works are made not simply to be looked at, but to be contemplated long and often, evidently the most fruitful moment and the most fruitful aspect of that moment must be chosen. Now that only is fruitful which allows free play to the imagination. …no movement in the whole course of an action is so disadvantageous in this respect as that of its culmination. …When, for instance, Laocoon sighs, imagination can hear him scream; but if he scream, imagination can neither mount a step higher, nor fall a step lower, without seeing him in a more endurable, and therefore less interesting, condition. We hear him merely groaning, or we see him already dead.

Again, since this single moment receives from art an unchanging duration, it should express nothing essentially transitory. All phenomena, whose nature it is suddenly to break out and as suddenly disappear, which can remain as they are but for a moment; all such phenomena, whether agreeable or otherwise, acquire through perpetuity conferred upon them by art such an unnatural appearance, that the impression they produce becomes weaker with every fresh observation, till the whole subject at last wearies or disgusts us. La Mettrie, who had himself painted and engraved as a second Democritus, laughs only the first time we look at him. Looked at again, the philosopher becomes a buffoon, and his laugh a grimace. So it is with a scream…this, at least, the sculptor of Laocoon had to guard against, even had a cry not been an offense against beauty, and were suffering without beauty a legitimate subject of art.

In politics, we are only enlightened as much as we demand one thing: happiness for every single citizen. This is the genius of modern politics, as far as we are able to make it happen.

Yet why are we so backwards when it comes to happiness itself?

Why all this progress in one area, and not in another?

In politics we demand universal happiness, and yet the equivalent in art, beauty, we moderns push away, as if beauty were limiting and old-fashioned. Picture for a moment politics which pushes away happiness. Art (no matter how hip it may appear) that pushes away beauty is just as backwards and fascistic.

The scale is a simple one: as one travels away from beauty one travels by law in one direction: towards the ugly.

Here is Lessing, from Laocoon again:

Be it truth or fable that Love made the first attempt in the imitative arts, thus much is certain: that she never tired of guiding the hand of the great masters of antiquity. For although painting, as the art which reproduces objects upon flat surfaces, is now practiced in the broadest sense of that definition, yet the wise Greek set much narrower bounds to it. He confined it strictly to the imitation of beauty. The Greek artist represented nothing that was not beautiful.

“Who would want to paint you when no one wants to look at you?” says an old epigrammatist to a misshapen man. Many a modern artist would say, “No matter how misshapen you are, I will paint you. Though people may not like to look at you, they will be glad to look at my picture; not as a portrait of you, but as proof of my skill in making so close a copy of such a monster.

The fondness for making a display with mere manual dexterity, ennobled by no worth in the subject, is too natural not to have produced among the Greeks a Pauson and a Pyreicus. They had such painters, but meted out to them strict justice. Pauson, who confined himself to the beauties of ordinary nature, and whose depraved taste liked best to represent the imperfections and deformities of humanity, lived in the most abandoned poverty; and Pyreicus, who painted barbers’ rooms, dirty workshops, donkeys, and kitchen herbs, with all the diligence of a Dutch painter, as if such things were rare or attractive, acquired the surname of Rhyparographer, the dirt-painter.

…Even the magistrates considered this subject a matter worthy their attention, and confined the artist by force within his proper sphere. This law of the Thebans commanding him to make his copies more beautiful than the originals, and never, under pain of punishment, less so, is well known. This was no law against bunglers, as has been supposed by critics generally, and even by Junius himself, but was aimed against the Greek Ghezzi, and condemned the unworthy artifice of obtaining a likeness by exaggerating the deformities of the model. It was, in fact, a law against caricature.

From this same conception of the beautiful came the law of the Olympic judges.

…We laugh when we read that the very arts among the ancients were subject to the control of civil law; but we have no right to laugh. Laws should unquestionably usurp no sway over science, for the object of science is truth. Truth is a necessity of the soul, and to put any restraint upon the gratification of this essential want is tyranny. The object of art, on the contrary, is pleasure, and pleasure is not indispensable. What kind and what degree of pleasure shall be permitted may justly depend on the law-giver.

We disagree with Lessing that “pleasure is not indispensable,” but note he is correct when he says that truth and science should be free—and here we should be free to urge that beauty in art correspond to happiness in politics.

Lessing goes on to emphasize the difference between painting and poetry:

A review of the reasons here alleged for the moderation observed by the sculptor of the Laocoon in the expression of bodily pain, shows them to lie wholly in the peculiar object of his art and its necessary limitations. Scarce one of them would be applicable to poetry.

Lessing was not given to easy generalizations, for he was immersed in seeing nature. After all, he writes: “For although a portrait admits of being idealized, yet the likeness should predominate. It is the ideal of particular person, not the ideal of humanity.” We will visit Lessing on poetry next, but we shall leave the reader with a final quotation from Laocoon, in which Lessing names the essence of amateur, philosopher, and critic.

The first who compared painting with poetry was a man of fine feeling, who was conscious of a similar effect produced on himself by both arts. Both, he perceived, represent absent things as present, give us the appearance as the reality. Both produce illusion, and the illusion of both is pleasing.

A second sought to analyze the nature of this pleasure, and found its source to be in both cases the same. Beauty, our first idea of which is derived from corporeal objects, has universal laws which admit of wide application. They may be extended to actions and thoughts as well as forms.

A third, pondering upon the value and distribution of these laws, found that some obtained more in painting, others in poetry: that in regard to the latter, therefore, poetry can come to the aid of painting; in regard to the former, painting to the aid of poetry, by illustrations and example.

The first was the amateur; the second, the philosopher; the third, the critic.

The first two could not well make a false use of their feeling or their conclusions, whereas with the critic all depends on the right application of his principles in particular cases. And, since there are fifty ingenious critics to one of penetration, it would be a wonder if the application were, in every case, made with the caution indispensable to an exact adjustment of the scales between the two arts.