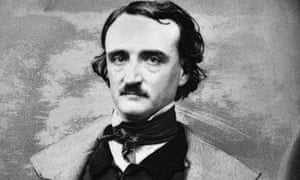

Edgar Poe was born on January 19, 1809.

Poe is a figure of opposites—which is what all successful people are.

First, it makes you enigmatic, which is always good, and it makes you enigmatic in a manner both complete and accessible, since opposites imply both depth and self-conscious unity, in a readily discernible manner. This will always make a character more attractive, and if not always appealing—some prefer consistency to complex magnitude—well, if today you don’t like this, tomorrow we’ll have its opposite. ‘I will always find a way to make you like me.’

Readers find Poe both emotional and mathematical.

One of his great themes was the double.

His essay on the physical universe, Eureka, was the first serious explanation of the Big Bang; it was read by Einstein, and Poe’s stunning scientific treatise is more influential than anyone will probably know. In it, we find the great opposites of the beginning when there is “nothing,” and the “bang” which produces “everything,” as matter expands into difference—which is how matter exists.

It is no surprise, then, that Poe’s detractors took to stealing from him those opposing qualities which make him truly who he is. He wrote humorous tales, but they focused soley on the ones concerned with murder. He laughed as often as he wept, but to suppress all that was great about him, all they had to do was appeal to our belief that he wept only, for we, the non-great, all share this low character—which takes delight in weeping for clowns and laughing at the sad. We laugh at Poe’s weeping, unable to accept he laughs, too. It makes us feel better. Genius, when experienced nakedly, has this way of making us, because we lack genius, feel miserable. And we don’t want to feel that. No one wants to feel overwhelmed by anyone. Hero-worship has a rule: it must have warmth and passion, but have a narrow, mean focus. Poe’s planet is both tropical and icy; but out of pride, we see him only as winter.

Poe is seen as ‘oddly this way.’ And therefore he doesn’t speak for us. He only represents a part of us. Poe has been damned with faint praise by the wise at Harvard and Oxford for so long, he is damned. He’s not perceived as one of us: an American speaking to Americans. But he was completely and soberly American in a time when Europe sneered at the upstart republic; Poe seems European, not because he strove to be that way; he was—and we have trouble seeing this—an American showing the world he could be anything he damn wanted. And seeming to be European was just one of his strategies. He lived and wrote for half his adult life in Philadelphia and New York, but somehow is boxed in as a Southerner who is a little too stiff, with a faint smell of gin, and worse, also falling into bohemian poverty which he hated—so on a personal level everyone has a reason to faintly dislike him. We’ve dressed him in borrowed clothes, in an outfit we’d like to think he wore—but Poe wears the world, the world doesn’t wear him. The default Poe that Americans “know” is not Poe, and since the private person belonging to his genius is to us a blank, the widely disseminated default simply lives on, reinforcing, inevitably, everything about him that is cheap and wrong. This happens to all of us; it’s just more magnified and unfortunate in a great writer.

For America’s sake, it’s a pity, because we lost somewhere in our Letters this true spokesman—who also happens to be one of the greatest geniuses who ever lived.

The opposites of good and evil will forever have a hold on our souls, not only in fiction, but in reality.

Poe was the Benjamin Franklin American good to colonialism’s world-cranking evil.

Poe belonged to the United States of America in its fragile, puritan, chaste, brilliant, heroic beginnings.

America is not the underdog anymore. But this is no reason to misunderstand and ignore America’s Shakespeare. Poe was not pretentious, so wouldn’t care, surely, that he’s B-movie popular. But ironically, no writer wrote for the educated few as much as Poe.

Whitman said America was “a poem.” But Poe, only 10 years older than Whitman, though he seems several lifetimes older, was America as “a poet.” Just as ‘America as a poem’ expands the definition of a poem, Poe’s ‘poet’ wrote more than poetry—murder mysteries (!) in which Dupin, an amateur, foils the chief of police, a professional. One coast of Poe barely knows the other. His laughing mountains barely know his sad valleys.

Britain, who had poets galore (America, before Poe, only school-boy imitators) was fast becoming the prose fact of the world. Places like India were colonized in reality, as America was colonized in the minds of brilliant but homely citizens like Thoreau and Emerson, who succumbed to the idea that locomotives were useless, even as U.S. manufacturing was the only thing keeping the United States free of colony status. Emerson (homely) and Poe (pretty) hated each other and Harold Bloom (homely) actually took up this quarrel, heavily on the side of Emerson. Anyone who does not consider themselves belonging to the world of locomotives will prefer Emerson, believing against all evidence that they are pretty, for taking the side of Emerson, simply because they are against locomotives.

America, with her locomotives, was the British Empire’s nightmare.

In Poe’s day, America was David to the British Empire’s Goliath, and the stone in David’s sling was not poetry; it was a locomotive. Poe was on the side of David and his locomotive, unlike Emerson’s friend Thoreau, for instance, who, unwittingly, by spurning the locomotive, sitting by his pond, played into the hands of the British Empire of colonies and holdings and farms and ponds and rivers and mines and booty and no borders. The romantic American belongs, at last, to Great Britain, and the Modernists, as Randal Jarrell surmised, were Romantics becoming so worldly they were no longer Americans—Henry James, T.S. Eliot, and Ezra Pound— globalist white men who sneered at Poe—the world’s great literary inventor—as provincial, immature, and backwater, so devious and self-assured were they. Eliot really let loose against Poe in “From Poe to Valery,” only after American-turned-British Eliot won his Nobel.

The “smart set” thought Poe “boyish.” But this is always how worldly, defensive neurosis dismisses a clear-eyed god.

Poe, as a critic, desired two things: Always be original. Never be obscure. He called Thomas Carlyle an “ass” for being obscure.

Poe was loudly and confidently Romantic-as-Modern; no antiquarian, Poe. Look at how he defines old versus modern long before “the Modernists” appeared, in his review of a British Literature anthology:

“No general error evinces a more thorough confusion of ideas than the error of supposing Donne and Cowley metaphysical in the sense wherein Wordsworth and Coleridge are so. With the two former ethics were the end—with the two latter the means.”

Poe prefers Coleridge to Donne. But Poe finally understood exquisite and delicate imagination is far more important in poetry than ethics. Which is an idea so new that almost no one believes it. Eliot, the leading critic of the 20th century, preferred Donne to Coleridge, and now ethics in poetry is everywhere, threatening to overthrow both fancy and imagination (which Poe, ever-grounded, said were closer than we think).

In his review of the British anthology edited by S.C. Hall, Poe quotes from four poems, the first of which he does not like, a much anthologized specimen you may know, by Sir Henry Wotton:

1

You meaner beauties of the night

That poorly satisfy our eyes,

More by your number than your light,

You common people of the skies

What are you when the sun shall rise?

2

You curious chaunters of the wood

That warble forth dame Nature’s lays,

Thinking your passions understood

By your weak accents; what’s your praise

When Philomel her voice shall raise?

3

You violets, that first appear

By your pure purple mantles known,

Like the proud virgins of the year

As if the spring were all your own,

What are you when the rose is blown?

4

So, when my mistress shall be seen

In sweetness of her looks and mind,

By virtues first, then choice a queen,

Tell me if she were not designed

Th’ eclipse and glory of her kind?

And here’s the last poem which Poe quotes, by Marvell, which Poe loves:

“It is a wondrous thing how fleet

‘Twas on those little silver feet,

With what a pretty skipping grace

It oft would challenge me the race,

And when ‘t had left me far away

‘Twould stay and run again and stay;

For it was nimbler much than hinds,

And trod as if on the four winds.

I have a garden of my own,

But so with roses overgrown,

And lilies that you would it guess

To be a little wilderness,

And all the spring-time of the year

It only loved to be there.

Among the beds of lilies I

Have sought it oft where it should lie,

Yet could not till itself would rise

Find it although before mine eyes.

For in the flaxen lilies shade,

It like a bank of lilies laid,

Upon the roses it would feed

Until its lips even seemed to bleed,

And then to me ‘twould boldly trip,

And print those roses on my lip,

But all its chief delight was still

On roses thus itself to fill,

And its pure virgin limbs to fold

In whitest sheets of lilies cold.

Had it lived long it would have been

Lilies without, roses within.”

Most of us either like, or dislike, old rhyming poems. Leave it to Poe to start a war between two old gems few would bother to distinguish from each other.

Of the first poem (Henry Wotton), Poe says,

“Here everything is art—naked or but awkwardly concealed. No prepossession for the mere antique…should induce us to dignify with the sacred name of Poesy, a series such as this, of elaborate and threadbare compliments…stitched apparently together, without fancy, without plausibility, without adaptation of parts—and it is needless to add, without a jot of imagination.”

Of the Marvell, Poe, in swooning rapture, calls “the portion of it as we now copy…abounding in the sweetest pathos, in soft and gentle images, in the most exquisitely delicate imagination, and in truth—as any thing of its species.”

Whether writing on the mysteries of the universe, the mystery of a stolen letter, or on the delicate accents of poetry, Poe is a literary treasure—strict but passionate.