![Image result for garden of proserpine]()

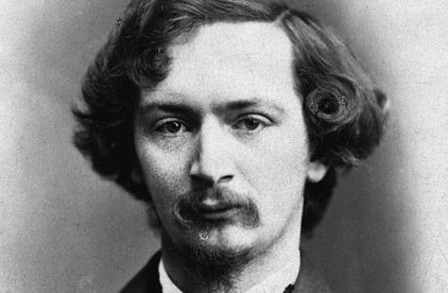

Algernon Swinburne was a decadent, mid-19th century, English aristocrat (Eton, Oxford), friends with the painter, and poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and art critic, John Ruskin. We are told he was diagnosed with a condition in which physical pain produced sexual pleasure.

Searching online, we find this: Swinburne’s book (Poems and Ballads) “included vehement atheism, sado-masochism, cannibalism, and lesbianism. In fact Swinburne may have been the first to use lesbian in its modern meaning, in the poem ‘Sapphics.’ The book was a huge success, but led to a charge of indecency placed against the book.”

In life, we care about the cause. We want to know the origins and secrets of a person, or a plan, or an idea.

In poetry, we care only for the effect.

Since a poet and a poem exist in the world, curiosity about cause may cause us to read for cause, but if this spoils our comprehension of the effect, it spoils our appreciation of the poetry. And yet does not comprehension belong to cause?

In what manner does a poem introduce us to the poet—the real person? What is a real person?

How much does this matter to us?

Can the poem make this not matter?

Does the poem hide the world, and its poet, and all which pertains to cause, to produce a better effect?

Or does the cause, the poet, and the world, always shine through the poem?

Here is “The Garden of Proserpine” by Swinburne:

Here, where the world is quiet;

Here, where all trouble seems

Dead winds’ and spent waves’ riot

In doubtful dreams of dreams;

I watch the green field growing

For reaping folk and sowing,

For harvest-time and mowing,

A sleepy world of streams.

.

I am tired of tears and laughter,

And men that laugh and weep;

Of what may come hereafter

For men that sow to reap:

I am weary of days and hours,

Blown buds of barren flowers,

Desires and dreams and powers

And everything but sleep.

.

Here life has death for neighbour,

And far from eye or ear

Wan waves and wet winds labour,

Weak ships and spirits steer;

They drive adrift, and whither

They wot not who make thither;

But no such winds blow hither,

And no such things grow here.

.

No growth of moor or coppice,

No heather-flower or vine,

But bloomless buds of poppies,

Green grapes of Proserpine,

Pale beds of blowing rushes

Where no leaf blooms or blushes

Save this whereout she crushes

For dead men deadly wine.

.

Pale, without name or number,

In fruitless fields of corn,

They bow themselves and slumber

All night till light is born;

And like a soul belated,

In hell and heaven unmated,

By cloud and mist abated

Comes out of darkness morn.

.

Though one were strong as seven,

He too with death shall dwell,

Nor wake with wings in heaven,

Nor weep for pains in hell;

Though one were fair as roses,

His beauty clouds and closes;

And well though love reposes,

In the end it is not well.

.

Pale, beyond porch and portal,

Crowned with calm leaves, she stands

Who gathers all things mortal

With cold immortal hands;

Her languid lips are sweeter

Than love’s who fears to greet her

To men that mix and meet her

From many times and lands.

.

She waits for each and other,

She waits for all men born;

Forgets the earth her mother,

The life of fruits and corn;

And spring and seed and swallow

Take wing for her and follow

Where summer song rings hollow

And flowers are put to scorn.

.

There go the loves that wither,

The old loves with wearier wings;

And all dead years draw thither,

And all disastrous things;

Dead dreams of days forsaken,

Blind buds that snows have shaken,

Wild leaves that winds have taken,

Red strays of ruined springs.

.

We are not sure of sorrow,

And joy was never sure;

To-day will die to-morrow;

Time stoops to no man’s lure;

And love, grown faint and fretful,

With lips but half regretful

Sighs, and with eyes forgetful

Weeps that no loves endure.

.

From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives for ever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.

.

Then star nor sun shall waken,

Nor any change of light:

Nor sound of waters shaken,

Nor any sound or sight:

Nor wintry leaves nor vernal,

Nor days nor things diurnal;

Only the sleep eternal

In an eternal night.

.

The first thing we notice is the dirge-like music, the calm, drugged delight which the verse produces. The second thing is the theme, which fits the calm, sad music—life is somewhere busy, but this place is sleepy. In this place (this poem with this kind of music) contemplation of sleep, and contemplation of death, makes us both satisfied and sad. The third, and final thing, is the monotony—there is no excitement, or climax, or glory—and again, this fits the theme—all is one enduring poetic sigh, without a real beginning or end.

.

The power of Swinburne’s poem is its three-part, self-reverential, aspect.

.

We detect no person, or personality in this poem—but a certain philosophy is expressed; its stanza-oriented verse, and more importantly, its verse-music matching its philosophy, is chiefly where its artistry lies.

.

Mary Angela Douglas is a living, Christian poet. Here is her poem, “I Wrote On A Page Of Light:”

I wrote on a page of light;

it vanished.

then there was night.

then there was night and

I heard the lullabies

and then there were dreams.

and when you woke

there were roses, lilies

things so rare a someone so silvery spoke,

or was spoken into the silvery air that

you couldn’t learn words for them

fast enough.

and then,

you wrote on a page of light.

Unlike Swinburne’s poem, a transcendence is evinced in three interesting ways—the existence of the “page of light” itself, the movement of the poem from day to night, and back to day, and the writing on the page of light. Nowhere in the entirety of the Swinburne poem is there a trope like this.

Swinburne’s poem smells of rot, and the poem of Douglas does not.

“The Garden of Proserpine” almost has a definite smell.

“I Wrote On A Page Of Light” is on a different plane of consciousness and experience.

The poems could not be more different.

Swinburne’s poem is enchanting, but has a few passages where the verse is clumsy.

The poem by Mary Angela Douglas is far more modest, but is mystically perfect, in a crystalline sort of way.

The moral force of “I Wrote On A Page Of Light” is stronger.

“The Garden of Proserpine” depends on music for its effect, and if the message seems monotonous after a while, it is not because of the verse, which is often beautiful, but because of the defects in the verse, which occasionally mar the composition.

Folks, we have another upset in Scarriet March Madness!

Mary Angela Douglas wins!