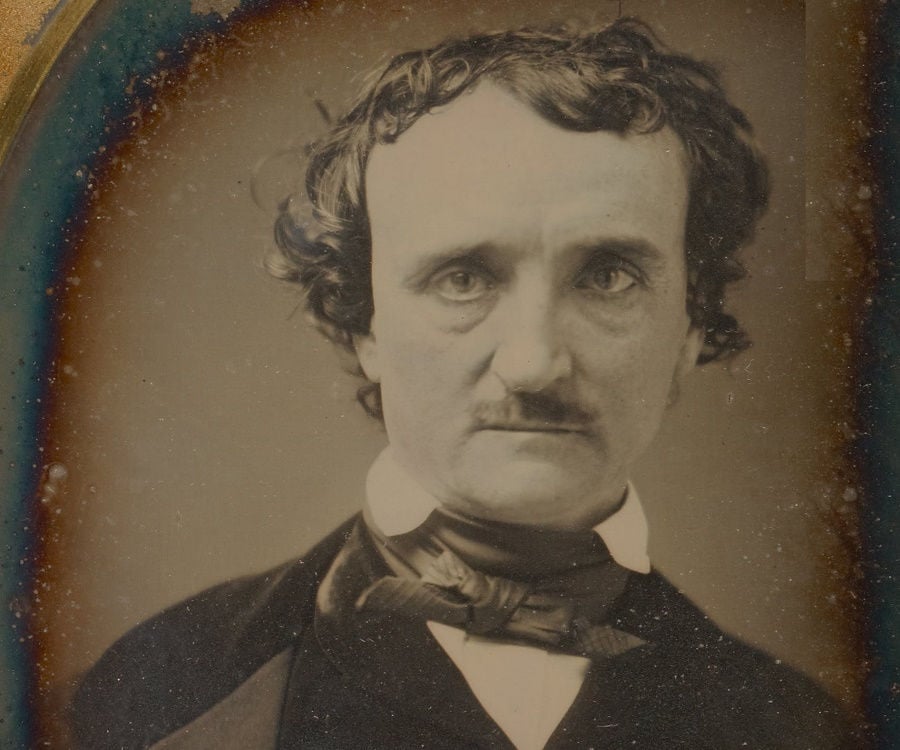

Poe, the first to clearly articulate the theory of the origin of the universe in the Big Bang (see his 1848 scientific essay, Eureka,) said a long poem does not exist.

Da Vinci—and we believe this is similar—said the point is the essence of geometry and painting.

Matter—and pain and sorrow—require relation. Put everything in a point, and you have pure spirituality without matter, and in the suffering and estrangement and separateness of the suddenly emerging explosion outward of matter (and the universe as we know it) we lose the point. Brevity is the entire concept in a nutshell—speed and speed-in-space mutually self-defining each other. Brevity is where Truth and Beauty live together. In the very word, brev-i-ty, 3 syllables sound with a velocity in precise ratio to the physical properties of the universe of that word. Brevity is the universe seen in a grain of sand, the soul of wit, and everything. Brevity is the flower genius crawls on. People who cannot stop talking are not geniuses; they make geniuses wince. Genius is the end of superfluous talk.

What if we applied Poe’s idea of brevity to life?

And not just brevity, but a decreasing dream we chase in our dreams?

Movies, for instance. We tend to remember films as a few brief scenes.

And more precisely: a favorite film tends to contain one arresting, favorite scene, and that scene contains one splendid moment we cannot forget: the scene within the scene: like the ever-fleeting moment of pleasure we, in the longer duration of our days, vainly seek—the point (invisible) within the point (slightly less invisible).

The point, as da Vinci felt compelled to tell us, has no substance—like the zero in mathematics which makes numbers exponentially increase; the point is more than infinitely small; it is smaller than small. It is nothing.

They say a great part of smoking’s addiction, or pleasure, is the fleeting, unsatisfying, nature of it, as you pull smoke into your lungs, feeling that faint jolt of warmth, the ever decreasing movement of the nicotine high, the whole strange act of the fire between your fingers, the fussiness of the habit which you own and owns you, alongside the stinky, unhealthy drawbacks—what is this pursuit but the search for the point—which exists, but does not exist—of the point, which is no point? A long smoke does not exist—though a habit of years, and all its fixings, is long.

The life of pleasure is like a pyramid.

The base of the pyramid is the sum of all our sensations.

As we travel up to the point at the top of the pyramid, with its decreasing volume, pleasure increases, and finally maximum pleasure is achieved at the top—and here at the apex of the pyramid is the vanishing point; the highest pleasure belongs to its end.

The pyramid, or triangle, belongs, as it happens, to perspective in painting; our sight, as da Vinci knew, lives in different triangles which expand outwards in mathematical precision from the eye. The point we seek is the nirvana of pleasure—but the point is also its end.

The triangulation of sight creates perspective—the soul of painting, geometry, and astronomy.

Perspective makes sudden sense of the chaos of sensation.

Ultimate pleasure is something we seek, but never find, and this motivates all movement and desire; the aesthetic translates the sweep and hurry of desire into the proportionate brevity of beauty—rather than allowing desperate desire to find the end, and its destruction.

Here is the summation of morality, art, religion, and civilization.

Limits on pleasure are necessary, but they can be either nicely, or crudely constructed.

Limits can be oppressive, and grow into a hatred of pleasure itself.

But if necessary limits on reckless and suicidal desire are hated, this can also result in loss of morals, taste, wisdom, aesthetics and vision.

Enemies of love exist on both sides.

Both sides aim for our doom—pleasure on one hand, and our protection against it, on the other.

Limits will always seem oppressive, even though they are necessary, and this is why Poe’s formula is the secret to wisdom and happiness—the idea of the brief poem enables us to love limits, and this is our salvation.

The greatest vanity of fake religion is that which puts the limitless universe within us. This is not a sign of God, but chaos. Understanding ourselves as small and limited and precise is what is truly godlike.

The brief poem is more beautiful and gives more pleasure than the long poem, for, as Poe wisely points out, we are physically unable to be greatly inspired for a long period of time.

As human beings, we are always calculating: how much expenditure of effort should I make for this amount of happiness? Is this the best bargain, the most pleasure, for my money, I can get?

And so Poe’s idea is a matter of the greatest practicality.

Now, when it comes to pleasure—the question always arises: will my pursuit of pleasure lead to all sorts of trouble? Unwise eating habits? A nightmarish, heartbreaking, violent, debilitating love affair?

But if we see that pleasure—which we blindly run after—exists in brevity, in very small pieces, or moments, we can more easily manage our reaction to its seductions.

The typical strategy is pretending seductions do not exist, or blocking them out completely. This may work for some, but not for the poet, not for the person who wants to experience pleasure.

How do we experience pleasure, yet mitigate the dangers and the follies?

By understanding the brief and elusive nature of pleasure. By understanding the seduction of pleasure (the point) is actually more real than pleasure itself (the point within the point). By managing our perception of pleasure, we can enjoy pleasure, and defy its punishments.

The first thing we need to do is to break up perception—and the experience of sensation—into brief moments of experience. The second thing is to realize this scattered existence is the real one, and all attempts to bridge moments into coherency is delusional and impossible. Coherency is based on a triangle. But this fact has nothing to do with happiness, so we should cease pretending, in these fake-profound religious sorts of ways, that the ultimate workings of life have anything to do with our happiness. Math is the answer. This is good news—math is comprehensible—and bad news—our long religious dreams are in vain.

As social creatures, who write long books, go for long walks, have long, flirtatious conversations, lie awake for entire sleepless nights, earn Ph.Ds, get married forever, make long term plans, and live in a long universe, we naturally unite moments in our minds, leaving out the less pleasurable, and more mundane, moments of the optimistic arc of our fantasies and dreams.

No matter how seduced we are, we can still reflect on how actually silly our desire is—the sweet rush of a bite of cake, which will eventually give us a stomach ache, or the grasping of that attractive body, which will eventually descend to bodily limit and boredom. But this is not to say we have to block or depress attraction—for suppression can make things worse; the strategy involves indulging in the beauty of the moment—so that beauty is experienced as it is best experienced—in its truly momentary state, where it can be appreciated without leading you into the dangers of trying to possess it—which we all know (unless we are a psychotic rapist, or some kind of debilitated addict), is impossible.

If we obey the law of brevity, we can feed our hungry minds—-and know this is all the luckiest get to have, anyway; we don’t succumb—and this is crucial—to jealousy of others, for this—jealousy of others, which is always a delusion—makes us act irrationally, more than anything else.

Gaze on that forbidden body part for a few seconds. That’s the best you will have, anyway.

Enjoy those eyes. You can never talk to them, or possess them. No one can. They belong to no one—but look at them, briefly, with pleasure.

The sun is not yours. Therefore enjoy it. It is too large to enjoy. But you can, because the sun, for you, is actually small.

Enjoy the placid and calm joy of not indulging, because actually, in stolen moments, you are indulging yourself with the greatest satisfaction. The point inside the point belongs to you. The point is not the point, but the point inside the point is yours, despite what everyone might say, those blabbing nonstop, who annoy you, those who may, or may not, be your dear friends.

Life is how you love your movie. Without being able to hold life (how it rushes by you!), you can enjoy those brief scenes, those brief moments of it—which is exactly how you enjoy your favorite films. You do get to eat your cake and have it—if you stop worshiping long movies and larger-than-life movie stars—and you make yourself in your own life by far the greatest film—which it is.

The long poem does not exist.

Only one life, with brief ones.