Rimbaud: Goes Against Catullus in Round One

Robert Frost is the no. 2 seed in the North—right behind Goethe’s no. 1 seed, ‘The Holy Longing,” the Romantic tour de force by the German titan. The famous Frost poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” is much beloved for its scenic beauty (yes, a few poems in just a few words manage that feat) with its clean, practical longing: “miles to go before I sleep.”

But look at this lesser-known poem, no. 15 “‘Follow Thy Fair Sun” by Thomas Campion, a 16th century poem which does battle against a 20th century one: a classic pre-Romantic versus post-Romantic battle, brought to you by Scarriet’s March Madness:

Follow thy fair sun, unhappy shadow,

Though thou be black as night

And she made all of light,

Yet follow thy fair sun unhappy shadow.

Follow her whose light thy light depriveth,

Though here thou liv’st disgraced,

And she in heaven is placed,

Yet follow her whose light the world reviveth.

Follow her while yet her glory shineth,

There comes a luckless night,

That will dim all her light,

And this the black unhappy shade divineth.

Follow still since so thy fates ordained,

The Sun must have his shade,

Till both at once do fade,

The Sun still proved, the shadow still disdained.

The trope is extremely simple: light and shade (“The Sun must have his shade”) with metaphysical, moral, romantic and metaphorical aspects attending its arc. The whole thing is lovely to behold, even if every last nuance is not quite understood.

The advantage the Frost has is “Stopping by Woods” shows, where “Follow Thy Fair Sun” tells. All great art, they say, shows rather than tells. Yet the Campion tells with such charm!

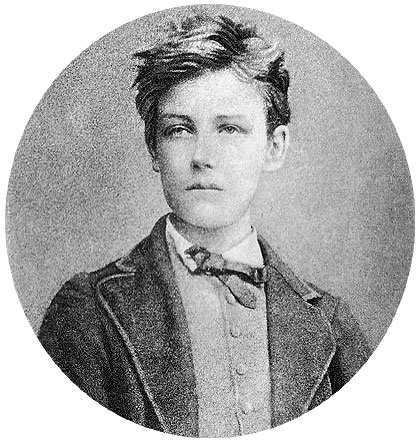

In our second match-up today, the no. 3 seed “Lesbia, Let’s Live Only For Love” by the Roman poet Catullus contends with “Lines” by the decadent, 19th century French poet, Rimbaud. If Catullus is Romanticism’s passionate root, Rimbaud is perhaps its rotten fruit.

The translation of Catullus is a Scarriet original, published for the first time on Scarriet:

Lesbia, let’s live only for love

And not give a crap

For jealous, old lips that flap.

The sun, when it goes down

Comes back around,

But, you know, when we go down, that’s it.

Give me a thousand kisses, one hundred

Kisses, a thousand, a hundred,

Let’s not stop, even during our extra hundred,

Thousands and thousands of kisses our debt,

But let’s not tell that to anybody yet.

This business will make us rich: kisses.

Old poems can get right to the point in a manner that today would feel too embarrassing. This is because invention demands ever more novelty, ever more variety and nuance, and the more contemporary must feed this requirement more, even if it means we never get straight to the point again.

The Rimbaud, written nearly two thousand years later, writhes in its nuances for the acute sensitivity of a jaded reader:

When the world is no more than a lone dark wood before our four astonished eyes—a beach for two faithful children–a musical house for our bright liking—I will find you.

Even if only one old man remains, peaceful and beautiful, steeped in “unbelievable luxury”—I’ll be at your feet.

Even if I create all of your memories—even if I know how to control you—I’ll suffocate you.

When we are strong—who retreats? When happy, who feels ridiculous? When cruel, what could be done with us?

Dress up, dance, laugh. —I could never toss Love out the window.

My consumption, my beggar, my monstrous girl! You care so little about these miserable women, their schemes—my discomfort. Seize us with your unearthly voice! Your voice: the only antidote to this vile despair.

We can get lost in the Rimbaud, a truly ‘modern’ poem: it does not march in a simple structure from A to B. Rimbaud’s ‘art’ is looser, but that looseness allows so much to be added! Yet since poetry is a temporal art, even loose poems have a beginning (A) and an end (B). We have to think Rimbaud is concluding with “voice” for a reason—the “voice” that saves us, the “voice” that is “unearthly” does not care for “schemes;” it is the expression of something unplanned, indifferent and apart. Heated and loose, the Rimbaud finally seeks a cold expression.

The Catullus really has a similar attitude: honest, crass, and heated as it ultimately loses itself in the coldness of mathematics. Rimbaud and Catullus are as similar as two peas in a pod, separated by two thousand years.

Frost and Catullus advance.

Frost 67 Campion 58

Catullus 60 Rimbaud 59